Here is Andrew Badinelli writing at National Review about guns:

Having a particular experience or set of feelings isn’t a substitute for rational argument.

I’m not a gun nut. I have never fired a gun, nor do I own one, and I don’t intend to ever do either. Guns never fascinated me as a super hero-loving kid, and they certainly don’t interest me now. In fact, I happen to be repulsed by the idea of hunting for sport. On paper, I might seem likely to be an enthusiastic cheerleader for Chris Murphy, my senator from Connecticut, as he leads the charge in the Senate for stricter gun control. But I’m not. That’s because my personal feelings about whether I want to own a gun are not pertinent to that debate.

In the wake of the terrorist attack in Orlando, our nation plunged into a sea of debates, ranging in topic from gun control to Islamic terrorism to immigration. And while these debates at times have been caustic, rash, or irrelevant, they are on the whole healthy for a democracy, especially one faced with an ongoing threat from terrorists.

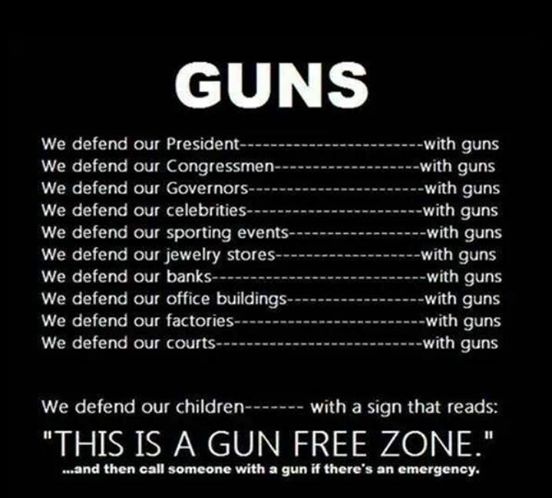

In our modern debate arena, however, rhetorical flashiness is often preferred to solid argument, solely because this flashiness lends itself to our culture of attention-grabbing headlines and viral regurgitation.

In last week’s New York Times, former infantry officer Nate Bethea offered his explanation for why he doesn’t think “assault rifles” should be available to civilians. In the piece, entitled, “I Used an Assault Rifle in the Army. I Don’t Think Civilians Should Own Them,” Bethea explains how he feels about guns such as the AR-15 (the civilian version of which is not an “assault rifle,” but set that aside) being commonplace in the United States:

These weapons are intended for the battlefield. I don’t want an assault rifle, because I don’t want to think of my home country as a battlefield. I don’t want civilians to own assault rifles, because I think the risks outweigh the rewards.

However, as David French pointed out, these feelings are just that: feelings, which shouldn’t be the basis for abridging the rights of others.

Read more: National Review