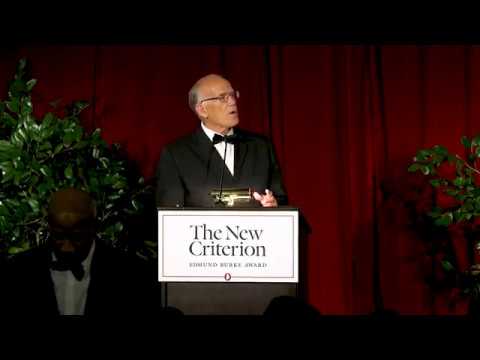

Here is The New Criterion featuring the video of a speech (below is an excerpt from the text) by Victor Davis Hanson:

On populism and the middle class.

Editors’ note: The following is an edited version of remarks delivered at The New Criterion’s gala on April 25, 2018 honoring Victor Davis Hanson with the sixth Edmund Burke Award for Service to Culture and Society.

Populism is today seen both as a pejorative and positive noun. In fact, in the present age, there are two sorts of populism. Both strains originated in classical times and persisted in the West until today.

One in antiquity was known as the base populism. It involved the unfettered urban “mob,” or what the Athenians disapprovingly dubbed the ochlos and the Romans disparagingly called the turba. Such popular movements were spearheaded by the so-called demagogoi (“leaders of the people”) or in Roman times the more radical popular tribunes.

These were largely urban movements. Protesters focused on the redistribution of property, radical democratization, taxes on the wealthy, the cancellation of debts, vast increases in public entitlements, and civic employment. The French Revolution and European upheavals of 1848 reflect some of the same themes. Today, Occupy Wall Street, Antifa, Black Lives Matter, and the Bernie Sanders phenomenon all stand in the same current. Often, urban intellectuals, aristocrats, and elites—from the patrician Roman Republican street agitator Publius Clodius Pulcher and the Jacobin Maximilien Robespierre, to present-day billionaires like George Soros and Tom Steyer—have sought to assist the urban protesters. Perhaps these gentleman- agitators thought they could offer money, prestige, or greater wisdom, thereby channeling and elevating shared populist agendas.

The antithesis to such radical populism was likely thought by ancient conservative historians to be the “good” populism of the past—and what the contemporary media might call the “bad” populism of the present: the push-back of small property owners and the middle classes against the power of oppressive government, steep taxation, and internationalism, coupled with unhappiness over imperialism and foreign wars and a preference for liberty rather than mandated equality. Think of the second century B.C. Gracchi brothers rather than Juvenal’s “bread-and-circuses” imperial Roman underclass, the American rather than the French Revolution, or the Tea Party versus Occupy Wall Street.

Read more: The New Criterion