This is the second in a series. The bulleted points below are culled from many sources. They are compiled to show how much information on an issue is available to those who are seeking it.

-

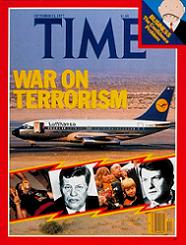

The threat of international terrorism is not new. It began before Iraq, before Afghanistan, and before 9/11. Thirty years ago on the cover of their October 31, 1977 issues both Time and Newsweek magazines featured the words “War on Terrorism.”

- Today we see the use of home-made improvised explosive devices. Tomorrow’s threat may include the use of chemicals, bacteriological agents, radioactive materials and even nuclear technology.

The beginning of understanding the war in Iraq is to understand what happened on 9/11. What happened was that we as a people were summoned back from a holiday from history that we had understandably taken at the end of the Cold War.

The beginning of understanding the war in Iraq is to understand what happened on 9/11. What happened was that we as a people were summoned back from a holiday from history that we had understandably taken at the end of the Cold War.

-

The horror of September 11, 2001 presented us with an enemy from the Dark Ages, the Islamic fascists who were our near exact opposites. They hate the Western tradition, and, more importantly, are honest and without apology in conveying that hatred of our liberal tolerance and forbearance.

-

They arose not from anything we did or any Western animosity that might have led to real grievances, but from self-acknowledged weakness, self-induced failure, and, of course, those perennial engines of war, age-old envy and lost honor — always amplified and instructed by dissident Western intellectuals whose unhappiness with their own culture proved a feast for the scavenging al-Qaedists.

-

Almost exactly sixty years passed from the October 1929 collapse of the stock market to the November 1989 crumbling of the Berlin Wall, sixty years of depression, hot war, and cold war, at the end of which the American people said: “Enough, we are not interested in war anymore.”

-

September 11, 2001 also showed us that we were in a war with a new kind of suicidal enemy, impossible to deter, melding modern science with a kind of religious primitivism.

-

Our enemy today has no return address in the way that previous adversaries had. Nazi Germany or Stalin’s Russia had return addresses. When attacks emanated from Germany or Russia, we could respond militarily or we could put in place a structure of deterrence and containment. Not true with this new lot.

-

Our enemy today refutes an axiom that has governed international relations for nearly 400 years (since the Peace of Westphalia – when the nation-state system began to emerge in Europe). The axiom was that a nation could only be mortally threatened or seriously wounded by another nation-by massed armies and fleets on the seas, and an economic infrastructure to support both. This is no longer true.

The reality of the threat:

- It is perfectly clear now that one maniac with a small vial of smallpox spores can kill millions of Americans. That is a guess, but an educated guess based on a U.S. government simulated disaster that started in an Oklahoma shopping center.

- Smallpox is a strange disease; it has a ten-day incubation period when no one knows they have it. We are mobile people, we fly around, and we breathe each other’s airplane air. The U.S. government, taking this mobility into account, estimated that in just three weeks, one million Americans in 25 states would die from one outbreak like that.

- Preemption is necessary but problematic. We have worries-and these are not new worries. In 1946, Congress held what are today remembered, by the few who remember such things, as the “Screwdriver Hearings.” They summoned J. Robert Oppenheimer, head of the Manhattan Project, and asked him if it would be possible to smuggle an atomic device into New York City and detonate it. Oppenheimer replied that of course it would be possible. Congress then asked how it would be possible to detect such a device. Oppenheimer answered: “With a screwdriver.” What he meant was that every container that came into the city of New York would have to be opened and inspected.

- In 2005, seven million sea-born shipping containers passed through our ports. About five percent will be given cursory examination. About 30,000 trucks crossed our international borders today. If this was a normal day, about 21,000 pounds of cocaine, marijuana, and heroin were smuggled into our country. How hard would it be then to smuggle in a football-sized lump of highly enriched uranium sufficient to make a ten-kiloton nuclear weapon to make Manhattan uninhabitable for a hundred years?

- To enrich uranium is an enormous, complex process that requires scientists and vast physical plants. But once you have it, making a nuclear weapon requires only two or three good physics graduate students. And there is an enormous amount of fissile material floating around the world.

- In 1993, some officials from the U.S. Energy Department, along with some Russian colleagues, went to a Soviet-era scientific facility outside Moscow and used bolt cutters to snip off the padlock – the sum of all the security at this place. Inside, they found enough highly enriched uranium for 20 nuclear weapons.

- In 2002, enough fissile material for three weapons was recovered in a laboratory in a Belgrade suburb.

- The Soviet Union, in its short and deplorable life, deployed about 22,000 nuclear weapons. Who believes they have all been accounted for?

-

Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, the portion of the War on Terror which has taken place in public view has been largely prosecuted far away from the United States, a fact which positively demonstrates the war’s success thus far in keeping terrorists away from the American homeland.

-

Unfortunately, the remoteness of known combat operations, combined with the lack of terrorist success in the United States, has had a disappointingly negative effect on Americans’ view of the war, and of the terrorist threat that still faces us. Terrorist activity has been taking place, and even more attacks have been publicly thwarted, in countries as geographically (and strategically) close to us as Canada, Spain, and Great Britain.

There have been several high-profile plots:

- On March 11, 2004, Islamist terrorists conducted a coordinated bombing attack on the commuter rail system in Madrid, Spain, killing 191 people and wounding a further 1,824. On July 7, 2005, four suicide bombers – known as the “Fantastic Four” to Islamists the world over who cheered their actions – struck three London underground trains and a double-decker bus, killing 52 people and injuring 770. In June of last year, seventeen militant Muslims were arrested north of our border after Canadian law enforcement officials learned that they were not only preparing to conduct a string of terror bombings across the country, but were also plotting “to storm Parliament, take hostages and behead the prime minister…if Muslim prisoners were not freed and if Canada did not pull its 2,300 troops out of Afghanistan.”

- In August of 2006, British authorities arrested twenty-five people who were plotting to smuggle liquid explosives aboard airliners bound for the US, with what was thought to be the intention of blowing them up over the Atlantic Ocean. In late October, though, it was revealed that the would-be terrorists’ actual plan was to wait until the passenger-laden aircraft were physically over American cities before detonating them, so as to “maximize the potential loss of life and economic effect.” Terrorism expert and Georgetown University professor Bruce Hoffman said the case “indicated that Islamic extremists remain focused on attacking U.S. cities.”

-

Intelligence is always the major American foreign policy and defense weakness, even in this era of extraordinary American economic, political and military strength. Faulty and inadequate intelligence is an ongoing and historic challenge – from Pearl Harbor to the USS Cole disaster to 9-11.

-

The problem has no perfect solution. Unless you know the future, surprise is inevitable. Limiting the more devastating effects of surprise is the elegant trick that defines the best-prepared.

-

Only gumshoe detective work, steady, tedious monitoring of terrorist suspects and the political will to either arrest or kill terrorists before they strike will stop a particular attack — maybe. We need all the help we can get from allies around the world.

-

Imagine the impact of a single nuclear bomb detonated in New York, London, Paris, Sydney or L.A.! What about two or three? The entire edifice of modern civilization is built on economic and technological foundations that terrorists hope to collapse with nuclear attacks like so many fishing huts in the wake of a tsunami.

-

Just two small, well-placed bombs devastated Bali’s tourist economy in 2002 and sent much of its population back to the rice fields and out to sea, to fill their empty bellies. What would be the effect of a global economic crisis in the wake of attacks far more devastating than those of Bali or 9/11?