Last week I updated my five-part review of Bruce Thornton’s book and posted it over at Barbwire.com. Here are the articles:

Excerpts From the Book ‘Eros—The Myth of Ancient Greek Sexuality’

Part 1: It’s Not Just Religion That Has a Problem With Homosexuality

Part 2: To Exercise Self Control or Not to Exercise Self Control

Part 3: Ancient Greeks Sounded A Lot Like Modern Christians

Part 4: Homosexuality — There is Nothing New Under the Sun

Part 5: Updates for Your Book of Epithets

Here was my new follow-up post:

What Would the Greeks Have Thought of ‘Gay Marriage’?

Having spent five articles excerpting Bruce Thornton’s book Eros—The Myth of Ancient Greek Sexuality, I wanted to also note an article on the topic by Robert R. Reilly that posted last year. Reilly is the author of The Closing of the Muslim Mind, and he is currently completing a book on the natural law argument against homosexual marriage for Ignatius Press.

The article, “What would the Greeks have thought of gay marriage?,” was posted at Mercatornet.com’s website. Reilly opens it with this:

It is ironic that the proponents of homosexuality so often point to ancient Greece as their paradigm because of its high state of culture and its partial acceptance of homosexuality or, more accurately, pederasty. Though some ancient Greeks did write paeans to homosexual love, it did not occur to any of them to propose homosexual relationships as the basis for marriage in their societies. The only homosexual relationship that was accepted was between an adult male and a male adolescent. This relationship was to be temporary, as the youth was expected to get married and start a family as soon as he reached maturity.

The idea that someone was a “homosexual” for life or had this feature as a permanent identity would have struck them as more than odd. In other words, “homosexuality,” for which a word in Greek did not exist at the time (or in any other language until the late 19th century), was purely transitory. It appears that many of these mentoring relationships in ancient Greece were chaste and that the ones that were not rarely involved sodomy. Homosexual relationships between mature male adults were not accepted. This is hardly the idealized homosexual paradise that contemporary “gay” advocates harken back to in an attempt to legitimize behavior that would have scandalized the Greeks.

Socrates, Reilly writes, “loathed sodomy”:

According to Xenophon in The Memorabilia (i 2.29f.), Socrates saw that Kritias was sexually importuning the youth of whom Kritias was enamored, “wanting to deal with him in the manner of those who enjoy the body for sexual intercourse.” Socrates objected that “what he asks is not a good thing.” Socrates said that, “Kritias was no better off than a pig if he wanted to scratch himself against Euthydemos as piglets do against stones.”

That’s not very nice, Socrates. Today some would call that hateful. Intolerance. Bigotry. Or just being a meany. Reilly continues:

In Phaedrus (256 a-b), Socrates makes clear the moral superiority of the loving male relationship that avoids being sexualized: “If now the better elements of the mind, which lead to a well-ordered life and to philosophy, prevail, they live a life of happiness and harmony here on earth, self-controlled and orderly, holding in subjection that which causes evil in the soul and giving freedom to that which makes for virtue…”

Like in our series on Thornton’s book, Socrates discussing the need for self-control and for “holding in subjection that which causes evil in the soul” sure sounds a lot like what Bible-believing Christians say.

By their chastity, these Platonic lovers have, according to another translation of the text, “enslaved” the source of moral evil in themselves and “liberated” the force for good. This was the kind of mentoring relationship of which Socrates and Plato approved. On the other hand, “he who is forced to follow pleasure and not good (239c)” because he is enslaved to his passions will perforce bring harm to the one whom he loves because he is trying to please himself, rather than seeking the good of the other.

In the Laws, Plato makes clear that moral virtue in respect to sexual desire is not only necessary to the right order of the soul, but is at the heart of a well-ordered polis.

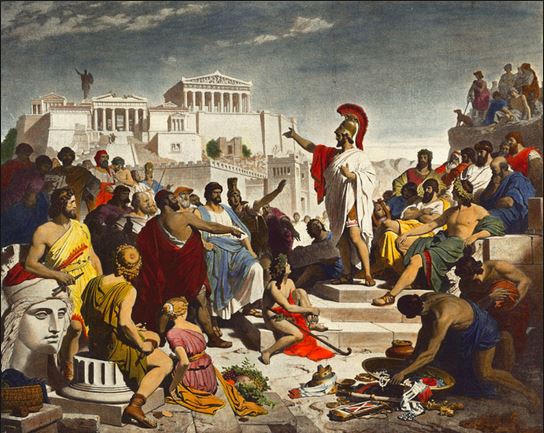

Moral virtue? Unrestrained pleasure at times being in opposition to “the good?” The idea that individual self-control is at the heart of “a well-ordered polis?” That sure sounds counter to modernity’s “enlightened” viewpoint. So it isn’t just today’s Christians, the Judeo-Christian ethic through centuries, and America’s Founding Fathers that discussed virtue as indispensable to civilization.

Again, here’s Reilly:

The central insight of classical Greek philosophy is that the order of the city is the order of the soul writ large. If there is disorder in the city, it is because of disorder in the souls of its citizens. This is why virtue in the lives of the citizens is necessary for a well-ordered polis. This notion is reflected in the Athenian’s statement concerning the political benefits of the virtue of chastity.

Here is Robert Reilly sounding a lot like Bruce Thornton in his conclusion about ancient Greek philosophy:

The lesson is clear: Once Eros is released from the bonds of family, Dionysian passions can possess the soul. Giving in to them is a form of madness because erotic desire is not directed toward any end that can satisfy it. It is insatiable. “That which causes evil in the soul” — in which Plato includes homosexual intercourse — will ultimately result in political disorder.

Did you think the “religious right” invented this notion of the importance of the family? Think again.

For Aristotle, the irreducible core of a polity is the family. Thus, Aristotle begins The Politics not with a single individual, but with a description of a man and a woman together in the family, without which the rest of society cannot exist. As he says in The Politics, “first of all, there must necessarily be a union or pairing of those who cannot exist without one another.” Later, he states that “husband and wife are alike essential parts of the family.”

Without the family, there are no villages, which are associations of families, and without villages, there is no polis. “Every state is [primarily] composed of households,” Aristotle asserts. In other words, without households — meaning husbands and wives together in families — there is no state. In this sense, the family is the pre-political institution. The state does not make marriage possible; marriage makes the state possible. Homosexual marriage would have struck Aristotle as an absurdity since you could not found a polity on its necessarily sterile relations. This is why the state has a legitimate interest in marriage, because, without it, it has no future.

So much for the “drop the social issues” argument. “[W]ithout households — meaning husbands and wives together in families — there is no state.” No state means no wonderful libertarian fantasy economy.

Social conservatives have the duty to take their fellow citizens to school so more people can understand the seriousness of the issues we defend. Sometimes the classroom takes us back thousands of years, and that trip back doesn’t always focus on the teachings of the Old Testament. During this and my previous five posts (one, two, three, four, five) we can see that often the subject matter highlights the writings of the ancient Greeks, the guys who share credit in the founding of Western thought.

I’ll let you read the rest of Robert Reilly’s article here. Enjoy.